Memes for freedom: Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty

A Snake for the new millennium

I’m not even going to comment on the length of these anymore, you just get what you get.

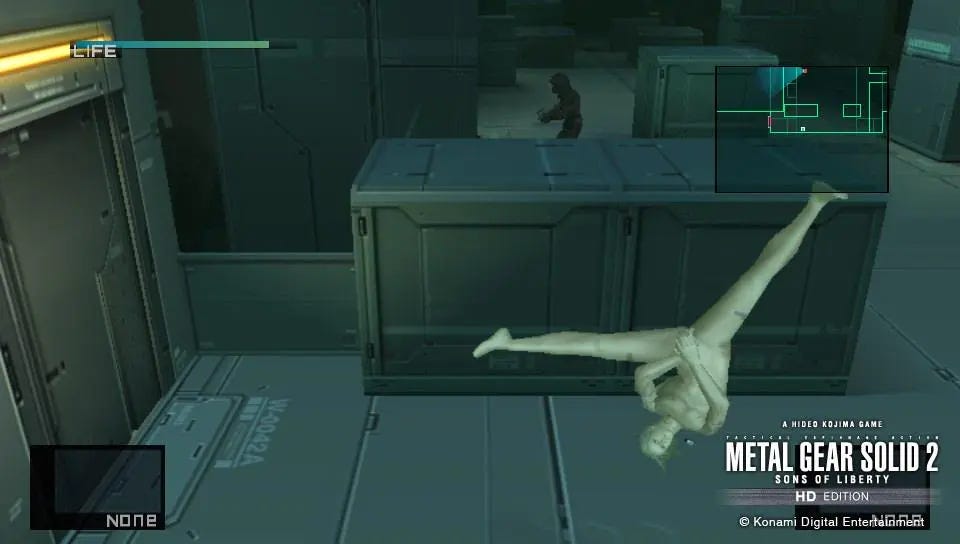

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty originally became infamous in 2001 for the bait-and-switch it performed with its main character, Solid Snake. All of the advertisements prior to the game’s release featured Snake, and fans were eager to get to play as the gruff macho-hero of the Metal Gear series in slick, 21st century graphics. It should be noted that Kojima delivered on these promises. The game opens on exactly the kind of bad-ass introduction of Snake that fans were expecting, and lets the player run through dozens of hapless mercenaries for the four or so hours it takes to complete the introductory tanker chapter. Snake is then promptly killed off, and the main part of the game opens on the real protagonist, Raiden, an effeminate and hapless pawn of the US military, who has never had any actual combat experience, having done all of his training in VR simulations. In all of the respects that mattered to the gaming audience of the early 2000s, Raiden is the complete mirror opposite of Snake. Raidens hair is long and white, his face is androgynous, and his sneaking suit is tight on his slender body and emphasises his hips, a far cry from the Kurt Russel inspired appearance of Solid Snake. Instead of doing a cool, tactical combat roll like Snake, Raiden cartwheels like a ballet dancer. The lady that Raiden talks to in order to save the game is not a shy young girl, who quietly pines for our hero, but his long-time girlfriend, who argues with him about his inability to remember their anniversary and his reluctance to open up emotionally. It cannot be overstated how much the gamers of 2001 fucking hated this guy.

Obviously, changing the protagonist was a calculated move by Kojima, who had seen how Solid Snake had become an icon of masculine videogame protagonists. To Kojima, this fixation had the unfortunate effect that women were alienated from the franchise, and Raiden was designed to be easier to relate to for women. Keeping the theme of MGS1 in mind, of struggling against your (biological and cultural) inheritance to find a peaceful existence, particularly in the face of the machinations of the military-industrial complex, Kojima probably also felt that people were missing the point by fetishising the white, hypermasculine super-soldier. An insanely obscure Metal Gear fun fact is that Raiden was actually teased in a previous game! Metal Gear: Ghost Babel for the GameBoy features a special piece of Codec dialogue mentioning that the player character has completed his training and then referring to them as Jack (Raiden’s real name). This bit of dialogue plays after all of the Special Missions are completed, implying that they were the VR training that Raiden did. Hiding secrets like this is a tradition throughout the Metal Gear series, often containing information that radically recontextualises events across several entries. Metal Gear Solid 3 will give us a good reason to discuss the fan-theories that place Revolver Ocelot as the architect of every significant event of the series.

Just as in previous games, we get a cast of tragic villains, who threaten to execute a devastating terrorist attack if their demands are not met, and a lone infiltrator from the elite foxhound unit under the command of Col. Campbell. The game is still in the strange kind of pseudo 2-D perspective from the previous game, although MGS2 incorporates more verticality and odd camera-angles. The gameplay is a more straightforward evolution of the gameplay from the previous instalment, including a lot of quality-of-life improvements. Aiming is smoother and easier, introducing a first-person aiming view, and movement has been freed from the eight directions of the d-pad, utilising the full spectrum of the analogue sticks. In addition to these are new mechanics that add details to the world along the lines of the graphical improvements. The sheer level of detail in this game is mind-boggling, and I highly recommend playing it simply for the joy of exploring how much stuff they put in there. The graphical and ludological improvements are even more impressive once we realise that MGS2 only came three years after MGS1, a production turnover for AAA-games that is almost unheard of then or now. Development also hit a snag on September 11, 2001, as planes crashed into the world trade center and the pentagon, making the planned parts of the game where a large flying base crashes into the world trade center appear in poor taste, which needed to be scrapped and replaced at the last minute.

Memetic desire

The mode of evolution in the Metal Gear series so far has been to repeat beats from previous games, but to give them a twist that embodies the overall theme of the game. For MGS2, Kojima decided to bring back the notion of bringing things back with a twist - with a twist! The repetition of tropes and set-pieces is folded into the narrative of the game, and is instrumental to the evolution of the themes of previous games. Whereas every previous game in the series, main-line or not, repeated set-pieces, the grand revelation of MGS2 is that the entire incident on the plant is a setup by an AI, controlled by the illuminati shadow government of the USA, to simulate the events of MGS1 to see if Raiden could be given the same kind of fame that Snake had achieved due to his involvement in the Shadow Moses incident. We thus get pretty much every event replicated, beat for beat, but this time with an overt narrative implementation, and a thematic relevance that rivals great works of literature. The problem of tarrying with ones constitutive determinations (ones thrownness in Heideggerian parlance), gathered under the notion of “gene”, got an uneasy solution in MGS1 of simply choosing freedom. It is hard to not see this as one of the few conceptual failures of that game, and something that kept the door open for the unintended role it received in the gamer culture of the time. It didn’t turn gamer culture toxic and misogynistic - gamer culture was doing that to itself - but it didn’t intervene in this culture either. MGS2 is an attempt to do just this, by making use of the concept at its thematic core: “meme”.

By the time of the Big Shell section, Solid Snake has become a meme in the game’s universe, just as he had become in ours. MGS2 puts the player in the role of the memer, of the person imitating (the origin of the word meme is the ancient greek mimesis) a certain notion that is passed on between people in a similar way to how a gene is passed down through inheritance. After the story of MGS1, Solid Snake’s exploits became public knowledge, and combined with his activity under his organisation Philanthropy, exposing the development of Metal Gear technology around the world, he was viewed as a super-soldier hero. This mirrors the status of Solid Snake in real world popular culture.

I think that it is most productive to analyse the memetic process in terms of Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of desiring-production, the basic entity of their process ontology, which is the instance of change. This instance has a three-fold character of production, recording, and consumption. These aspects are all themselves productions, the production of a product, the production of a record, and the production of a consumption. Add to this that it also always involves the production of desire. This characterisation is precise, but difficult to make intuitive sense of. Desiring-production is the name of the locus of change, that is, it is how things happen in the most general sense whenever a change occurs. Whenever production is mentioned, it is always the production of a change, of something new. A helpful picture might be to think of desiring-production as a black box, with inputs and outputs, transforming the information that passes through it, and acting as a record of this change. The main contention of Deleuze and Guattari is that any change involves a surplus of desire. This was in opposition to the dominant Lacanian view of the time, stating that desire always involves a lack - Deleuze and Guattari maintain that desire is immanent, productive, and self-sufficient, i.e. it doesn’t need any complex structure to emerge from, and whenever it emerges, it is always the same.

The memetic process occurs when the meme is reproduced, that is, when an idea or behaviour is copied or imitated. When Raiden reproduces the meme of Solid Snake, he takes in certain ideas and images about him. This makes an impression of him, it affects his beliefs and desires, and he thus becomes a record of the meme. When he reproduces the meme, he thinks and acts in a way that imitates Solid Snake, allowing the meme to be transmitted further to other people, now slightly altered. This process is also the production in Raiden of the desire to act and think in this way, and of the desire for a world in which it can come about. The problem of freedom reemerges here, not as freeing oneself from the burden that one was saddled with from birth, but as the struggle to even relate to others clearly, and to make decisions of ones own volition. The brilliancy of the Metal Gear series has been how its themes are simultaneously integrated on the ludological side as well as the narrative/cinematic side, and MGS2 even manages to integrate its nature as a sequel, as a shinier reproduction of an action game and the feeling this imparts on the player, into its overall message. Again we get an apparent ludonarrative tension, that we should disregard the memetic nature of the game, only to have this tension utilised to great effect and properly resolved in its conclusion.

Using cool videogames to deal with the trauma of post-modernity

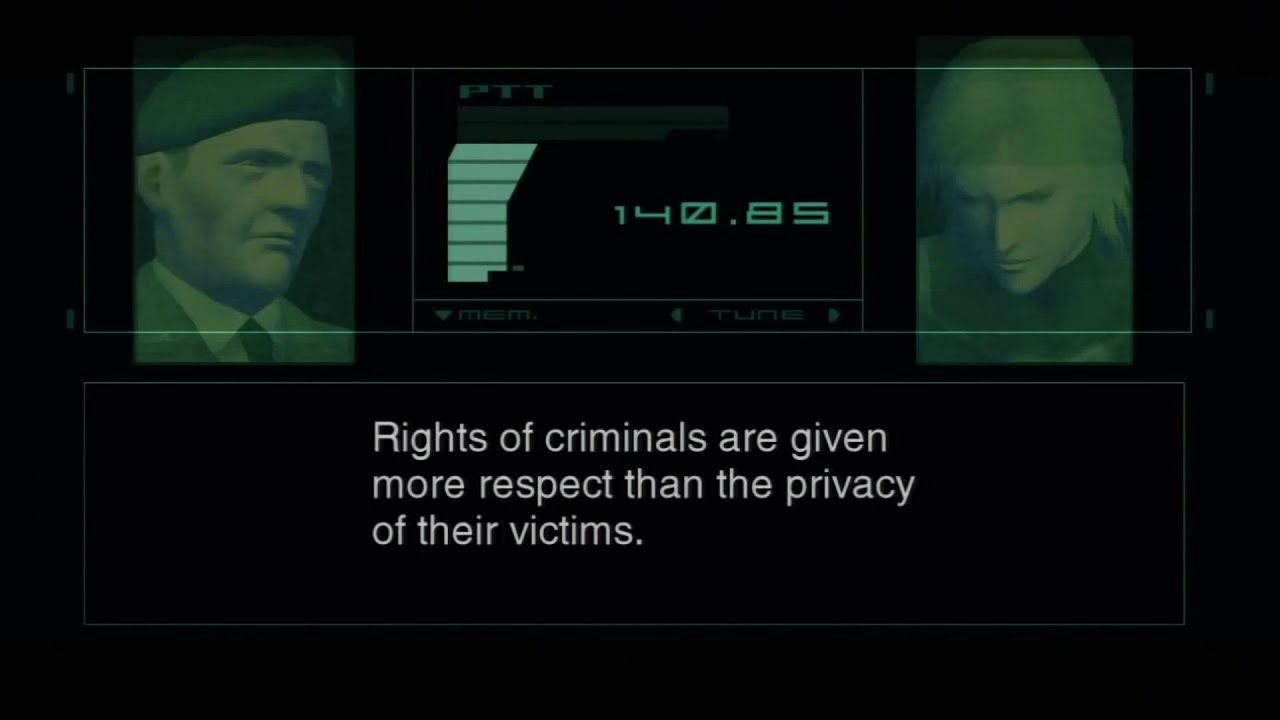

Existing in the postmodern condition, we live with the “knowledge” that no overarching, grand narrative can make ultimate sense of the flow of history - that there is no meta-language, which can discern truth from falsity in every situation. Rather the affect of truth is always a construction, and one that can be wielded to suit ones needs. The game expresses this in a sequence with an unprecedented prescience, the final codec call of the game, that has been called “the most profound moment in gaming” by our friend Max Derrat, and that has made MGS2 the subject of endless analysis. The true purpose of Arsenal Gear, the giant superweapon vehicle that our heroes have to destroy, is to house an AI, that is designed to control the flow of information on the internet, to sway public opinion by reshaping the context around events, and to fabricate truths to keep the current elites in power. Over a decade later, in the time of Trump’s ascension to the presidency, when everyone was talking about the arrival of the “post-truth” society, the extrapolation of MGS2 on the effect that the internet would have on politics seemed downright prophetic.

It seems to me, that most analyses of MGS2 focus on this postmodern diagnosis, and couple it with the attitude of the most famous philosopher of postmodernity, Derrida, and his deconstructionist approach. The method of deconstruction aims to disintegrate the efficacy of judgements, by showing how there is an incommensurable difference between the concept of the other and any (set of) intuition(s) about them, and thus deferring the assignment of meaning to a point when there may be found an intuition that is adequate to the concept of the other (which is impossible and always postponed). Its insistence on the textuality of anything available to us traps us in a world of incommensurably foreign others, which can only be sublime, and which we must take the utmost care to never violate (leading to the deconstructionist, Derridean shenanigans going on with people claiming that the world revolves around receiving the forgiveness of an other (for what is unknown, presumably sneezing in their vicinity (these people need to touch actual grass))). What this approach misses in the eyes of any reasonable social theory is the libidinal efficacy of language, which works its effects on us irrespective of our attempts to show its incoherence. The only to producing such an effect, given the absence of any ultimate method, is through aesthetics. You can take your pick of Guattaro-Deleuzian, Zizekian, or any other fairly relevant approach and get this point. When MGS2 (or any work of art) is caught up in the deconstructionist approach, it either gets reduced to an example of a work that exists to convey an understanding of the postmodern condition, or it is deemed so significant that it is shifted into the mode of a sublime object, whose meaning is always deferred. The result of either is that the artwork is neutered, its affect on the player neglected.

When we analyse MGS2, or any game or other artwork for that matter, we should always take account of the most significant ways that it affects us. MGS2 effectuates a reflection in the player of the ways that our worldviews are swayed by factors beyond our control, not merely as a formulation of how “truth is impossible” in the postmodern condition, but as a player in the game of building the world. The experiences that you have going through the game, which are a complex of the ludological and the narrative/cinematic aspects, all together constitute its own memetic process, leaving an affect that is the surplus of desire for a world in that is compatible with it. The narrative meaning of any Call of Duty game is that war is bad for you, with some justified war doctrine mixed in to excuse the events of the game. The affective meaning of any Call of Duty game, all aspects considered, is that war is great fun, and that you should participate in it with a good conscience - after all, through your experience from playing the game, you have already become something of an expert. This is why the US military uses the franchise to recruit young people. If there is one message that Kojima has insisted on conveying throughout the entire Metal Gear series it is a steadfast anti-military and anti-war attitude. This, more so than his penchant for mechs or his foot-fetish, is his meme.